As we observe Universal Health Coverage day, it’s time to look again at gender barriers to health care, and particularly health care for chronic diseases.

Monowara lives in the Khulna Division of Bangladesh. A mother of four, she is from a rural community experiencing significant levels of poverty. Now in her sixties, she spent 13 years with cataracts and deteriorating vision, unable to fully participate in community life and see members of her family clearly. Eye disease has been found to be almost 35% higher among women than men in Bangladesh, yet the surgical coverage rate for cataracts is more than 12% lower in women .

Observations of Universal Health Coverage (UHC) Day on 12 December will surely focus on how far we remain from the attainment of the SDG goal 3.8 of UHC for all by 2030.

In that context, it’s important to examine how gender inequality continues to pose a barrier to UHC for women and girls – particularly for prevention and treatment of non-communicable diseases which have not traditionally been part of the standard package of womens’ and girls’ health services.

Many aspects of gender inequity are easy to see. Women and girls globally are more likely to be living in poverty, working low-skilled jobs for inferior rates of pay, providing unpaid care for their families, facing barriers to education and proper nutrition, or withdrawn from education should there need to be a choice between siblings of different genders. They are much more likely than men to face gender-based violence.

Beyond ‘bikini’ medicine

Other aspects of gender inequity are ‘invisible’. The term ‘bikini medicine’ describes the mistaken belief that women’s health only differs from men’s in the parts of the body that a bikini would cover.

Our focus on reproductive health blinds us to broader gender differences – in risk factors, in access to care and health promotion, and in health outcomes. Around the world, girls and women living with NCDs experience specific challenges in accessing prevention, early diagnosis, treatment and care, particularly in low-resource contexts; for example, low prioritization of female health within families, women’s limited access to financial resources to cover the costs, their caring responsibilities, and restrictions on their ability to travel freely, to name a few.

India’s example: more insurance payouts to men than women

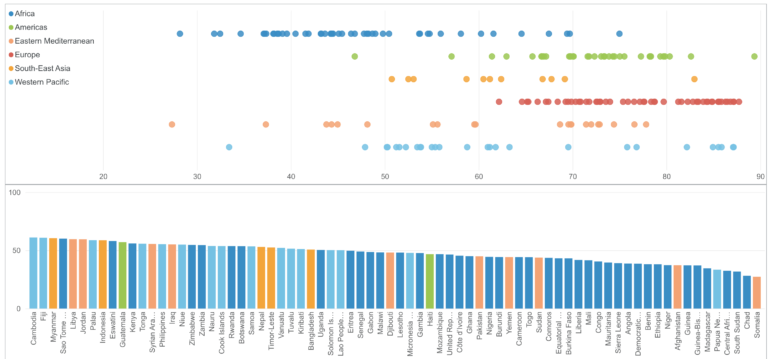

This can lead to stark gender differences. For example, an analysis of national data collected by India’s Insurance Information Bureau found that while more women were covered by government-funded health insurance schemes than are men, a staggering 70% of insurance pay-outs went to males. Barriers to accessing care are compounded by health systems that may fail to respond to the specific needs of girls and women with NCDs; either because they are not considered ‘women’s diseases’, or because gender differences in the way they are experienced are not understood.

For example, women are less likely than men to receive recommended medication after experiencing a heart attack. Women having a stroke are more likely than men to be wrongly diagnosed, and despite widely reported sex- and gender-based differences in asthma and asthma management, these issues frequently are not considered by health care professionals.

All this points to a need to address barriers to accessing health services for women in particular. We need to recognise gender as a determinant of health; for example, through the obstacles women face to adopting healthy lifestyles, such as unsafe environments that restrict their opportunities to be physically active. We need women-centred policies and programs focusing on prevention and care across the life course, prioritised to address the inadequacy of current systems. As the eyes of the global health sector turn to the High-Level Meeting on Universal Health Coverage in 2023, we must look anew at what’s needed to deliver effective, targeted services for both women and men.

Prioritize better data collection, service integration and women’s leadership

We suggest three key priorities:

- Disaggregated data and analyses – The gender inequities highlighted here are just the visible tip of a likely enormous iceberg, which remains hidden because we lack the data needed to identify these and other, intersecting inequities related to age, race, ethnicity, sexuality and so on. We urgently need data disaggregated and analysed by gender and other characteristics in order to effectively identify and break down barriers to health services access.

- Integration of services – Leveraging health infrastructure built for maternal and reproductive health can be an effective way to reach women with other services; for example, by incorporating screening and treatment for diabetes and high blood pressure into routine pregnancy checks.

- Women’s leadership in health – Despite making up close to 70% of the health workforce globally, women are underrepresented in health sector leadership, with only 25% of women in decision-making positions. Adequate representation of women at the top would ensure policies, programs and laws more fully consider the experiences and perspectives of half the population.

Monowara’s untreated cataracts were spotted when she accompanied her daughter Munni to a maternal and child health clinic which has integrated eye care into the services it offers, training MCH workers to detect basic eye conditions. Monowara’s eyes were checked while Munni was nursing her newborn baby, and her cloudy lenses were subsequently replaced with new ones in a relatively simple, 20-minute procedure, which was provided to her for free.

Both are simple examples of service integration that can be transformative for the individuals involved.

The impact on Monowara’s life of being able to see clearly again after 13 years is immeasurable; not just for her, but for her entire family. Only by lifting our sights to the full picture of women’s health – including gender differences beyond the ‘bikini’ and across the life course – and by investing in women’s leadership and a whole-of-government approach to tackle deep-seated gender inequities across the board , can we hope to achieve the vision of universal health coverage for all.

Author: Jane Madden is the chair of The Fred Hollows Foundation, Dr Monika Arora is the vice president of the Public Health Foundation of India and President-Elect of the NCD Alliance and Emma Feeny is the global director of impact & engagement at Australia-based George Institute for Global Health

Source/this news was originally published on the website of the Health Policy Watch and is reproduced here with their kind permission.